by Alice Daniel. Alice reported this story for KQED public radio’s statewide “California Report,” as part of a Journalists in Aging Fellowship supported by New America Media, the Gerontological Society of America and the Silver Century Foundation. This story was first published by New America Media.

Click to hear the radio report of this story.

Dia Yang is a cultural broker at the Fresno Center for New Americans. She helps Southeast Asian refugees acclimate to the United States.

On this rainy day, she’s working with a dozen older Hmong men and women who find life in America really hard.

Yang instructs them in a crafts activity: decorating little paper gift boxes to fill with chocolate and give to a friend or relative. “It’s something to uplift them and keep them in the present moment,” she said. “And it gives them a chance to just be with each other.”

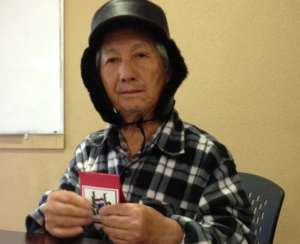

Yong Yang Xiong fought in Laos for six years in the CIA’s Secret War. He does group crafts to help deal with depression. (Alice Daniel/KQED)

Yong Yang Xiong, 66, works on a red paper box at a long table littered with art supplies. Like the others here, he also goes to a weekly therapy group to talk about his problems.

“When I come here they [counselors] help me out. I’m not just by myself but in a group and everybody shares, and that helps ease up the depression,” said Yong Yang through an interpreter.

Rampant Depression

Ghia Xiong is a psychologist with the center. He said activities and group therapy sessions provide peer support and help with depression, which is rampant in this population. Life is so different here, he added, and all the worries about money, jobs and transportation often lead to feelings of hopelessness and helplessness.

Xiong recalled life back home was much simpler “just as long as you have a field to farm, and a jungle where you can go hunt and get food, and a river where you can get fish for your family.”

Back home is Laos. The Hmong knew the land well and were instrumental in helping the CIA fight its secret war against the communists. When the long war ended, tens of thousands of Hmong were deserted. They fled on foot to refugee camps in Thailand and eventually resettled in the United States. The second wave of refugees arrived only 13 years ago — among them was Yong Yang Xiong.

Ghia Xiong caid there are many refugees like Yong Yang. “So now they’re carrying all this and they’re coming to therapy and we say, ‘Let’s talk about things that are really troubling to you,’ and they’re saying, ‘Do I trust you, are you sure you’re going to keep it confidential?’ I don’t know what confidentiality means. I mean that doesn’t exist in our culture.”

Xiong observed that it takes a very long time for most clients to open up even a little bit, to just scratch the surface of their sorrow. It’s almost anathema to their culture to talk about their deepest feelings.

Counselors at the Center for New Americans lead group activities with clients suffering from depression. The clients chose not to be in the picture. (Alice Daniel/KQED)

The Best Therapy

It’s why group therapy is the best option at first, he said, because it gives them some basic tools to talk about themselves with the support of their peers. “Many do not understand yet or are not ready for individual therapy. They may not have the necessary resources or skills to really begin exploring depression,” he said.

Almost every older client, most of them in their mid-50s and 60s, comes into the center with symptoms of depression.

Part of Yong Yang Xiong’s depression comes from so much physical pain. He fought for six years in Laos.

“As a petite man, I was given very heavy loads to carry for days and nights,” he said. “This is a reason why physically I’m not well now. I have a really bad back. It’s been bothering me a lot.”

Yong Yang lived in refugee camps for 26 years before coming to Fresno. He wanted to get a job but employers said he was too old, and he couldn’t speak English.

All of this stresses him out. Sometimes he’ll take an anxiety medication. “When I feel like I’m very depressed, I take the medication so it kind of like eases my mind, kind of like I’m slowly not thinking about all the stress and pain that I have, so it helps from time to time.”

The language barrier also makes him and other Hmong elders feel isolated. During group activities at the center, they have a chance to talk with each other about that isolation. Joua Thao, a college student who is interning here, points to a woman putting a sticker on the paper gift box she’s just made.

“She chose an owl because she only knows Hmong, and then her grandson only knows English, and then the only thing they both know is ‘owl,’ ” Thao said. It’s the grandmother’s way of reaching out to her grandson.

Culturally Sensitive Mental Health Care

For the past nine years, the center has offered culturally sensitive mental health services for hundreds of refugees with depression under the state’s Mental Health Services Act, or Proposition 63. The program is called Living Well or Kaj Siab in Hmong. Counselors say Kaj Siab means to feel better, to see a better light at the end of the tunnel, to have better self-esteem. It’s a term that makes more sense to the Hmong than mental health. Aside from therapy groups, the program also offers community gardening and wellness walks.

The Living Well Program not only works with Hmong but with other Southeast Asian communities, including Lao, Cambodian and Vietnamese. Ghia Xiong said depression is also rampant in these groups.

And while the center has helped a lot of people, Xiong worries that there are many who are not seeking help or don’t even know that help exists. Now the center is starting to go to where people live. It just got a grant through the California Reducing Disparities Project to hire a program director, Melanie Vang.

“Part of my role is to do recruitment, through Hmong radio, Hmong TV, or through house visits or connecting through friends and families,” Vang explained.

On this day, she’s asking to visit the home of a widow she’s heard is depressed. There’s a branch of greenery hanging from her door.

“Culturally if they have some kind of a green thing on the door, we normally have to ask them if we can go inside the house because spiritually the door is locked,” she said.

It means the family is protecting the house from bad spirits and may not let us in. But the door opens and we are allowed inside.

Pa Vang lives in this home. Pa means flower and there are artificial flowers and photos everywhere. But she can hardly see them because she’s going blind. She’s got diabetes; it’s so bad she needs dialysis. Her husband died a few years ago.

She used to be a home health aide and an activist in the Hmong community, but now the days are long for her. Listening to Hmong folk music helps. Melanie interprets for her.

“By listening to the music, I was able to at least kind of like ease myself out of pain and stress and depression,” Pa said.

Melanie suggests Pa come to the Fresno Center for New Americans to try out some of their services, and maybe even group therapy. Pa is receptive to the idea.

“I would like to attend some of these program to help me. However, I have dialysis three times a week. And now that I have a visual problem, I cannot drive,” she stressed.

Melanie Vang tells her the center plans to provide some transportation for clients in the near future. And hopefully, that will mean one less door for her to knock on.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Diverse Elders Coalition.